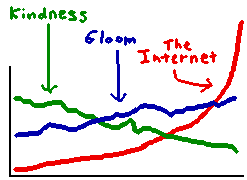

(Graph from Robert Orenstein, by way of Jim Blandy.)

A recent conversation on an open source mailing list reminded of two fallacies I’d been wanting to write about. (And what is a domain like “rants.org” for, if not the debunking of fallacies?)

The first fallacy is that bugs are bad, or rather, that growth in the number of bug reports in your bug tracker is bad. The second fallacy is thinking of bugs as a form of technical debt.

Taking them one at a time:

Seeing bugs in your tracker is not bad news — bugs, in the aggregate, are good news.

The number of bug reports is proportional to the number of users, not to the number of defects.

This doesn’t mean projects should ignore bug reports, of course. It just means that you shouldn’t be alarmed as the number of bugs in your bug tracker increases. Bug growth is a sign of success: you’re getting users. The bug report rate is a proxy for the user acquisition rate.

The corollary is: you cannot expect to close all the bugs in the tracker. In fact, you shouldn’t even want that, because if you were to succeed, it would mean you’re not getting new users anymore.

This is counter-intuitive. All programmers want to fix every bug they know about; none of us want to ship with known bugs, though we always do. What does it mean if we can’t close every bug in the bug database?

A healthy project is in a constant state of triage between bugs and feature development, and the bugs must not always win. A project can’t let the bug database determine how developers spend all their time, any more than an individual person can let their email inbox determine how they spend all their time. If you’re not expecting to close all the bugs, and you want to acquire more users (so you can get more bugs), then you have to both fix bugs and add or improve features, and you have to be fundamentally comfortable with an ever-growing database of bug reports.

Think of it this way: every unimplemented feature or improvement is also a bug, in a broader sense, whether it’s filed as such in the tracker or not. It is an absence of something that should be present in the software. So if you manage to close out all your bugs, but you ship without that improvement, then you’re still shipping with a bug, you’re just calling it something else (or not calling it by any name at all). Shipping with no bugs at all is therefore impossible for any active project. It might be theoretically possible for some extremely narrowly-scoped project, but by definition such a project would not be “active”: it would achieve its goal and then remain static and perfect forever. Chances are this does not describe most projects you work on.

One of the big fears developers have is that an ever-growing bug database will overwhelm them — that they’ll spend all their time triaging bugs, asking reporters for more information, etc, and not enough time actually developing. This fear is not groundless: if every bug report is seen as a crisis requiring the attention of a core developer, things will grind to a halt as soon as there are too many users. The trick is to have tools that enable the community as a whole to manage the bug database with increasing economies of scale, instead of expecting developer attention to scale. (Apport and Launchpad’s inline dup-finding are two examples of such techniques, and there are many others.) The number of technically-inclined users who can help out with bug management will grow roughly proportionally with the number of users who are inclined to file bugs at all. So if the project provides ways for the first kind of user to participate, the second kind of user will be a help not a hindrance.

It’s true that core developers will need to spend a greater percentage of their time on bug triage as a project matures, but that percentage eventually hits a ceiling and levels off — after all, it has to, since there’s no way a developer can spend more than 100% of her time managing bugs, and yet the rate of incoming bug reports is going to increase with users. So if a developer is going to spend less than 100% of her time on bug management by definition, she might as well choose what percentage it’s going to be, since she’s going to not touch an arbitrary (and increasing) percentage of reports anyway.

Emotionally, this can be difficult for developers, because we are tempted — the second fallacy — to treat bugs as technical debt. In the mailing list conversation I referred to earlier, this equation was made explicitly, and it’s not the first time I’ve seen that happen. But I think it is a category error.

Bugs and technical debt are entirely different things. Fixing a bug may reduce tech debt, leave tech debt unchanged, or even increase tech debt, depending on how the fix is done.

Technical debt is a great concept. As far as I know, it was first introduced by Ward Cunningham (yes, that Ward Cunningham, the person who invented wikis):

Shipping first time code is like going into debt. A little debt speeds development so long as it is paid back promptly with a rewrite… The danger occurs when the debt is not repaid. Every minute spent on not-quite-right code counts as interest on that debt. Entire engineering organizations can be brought to a stand-still under the debt load of an unconsolidated implementation, object-oriented or otherwise. [1]

In other words, all those places in your code where there are comments like "FIXME: this duplicates code in turtles.c; we should really abstract this out" are tech debt. You pay interest on the debt whenever you have to make changes to code that is not as well-factored and maintainable as it could be. You pay back the debt when you finally refactor that code and remove the FIXME comment.

A bug is something completely different: it’s an instance of the software not behaving the way the developers or users expected. You could even increase technical debt by fixing a bug, if you improve the program’s behavior in a way that reduces the overall maintainability or cleanliness of the code (that’s how all those FIXME comments got there in the first place!).

So do not think of that swelling bug tracker as a debt that needs to be paid back. It’s not. It needs to be managed intelligently, and there are many techniques for doing so. But it’s going to grow, and if your project succeeds, it’s going to grow forever. Trying to suppress that growth (for example, by discouraging filings from all but technically qualified reporters) simply squelches a useful information source. Far better to know how many bugs are coming in, how fast, and of what nature, so you can understand how your user base is growing and develop appropriately scaled statistical mechanisms for handling the problems they encounter. Thinking of that information as a debt, rather than a resource, can cripple your project.

For an interesting contrast, in the Postfix project, there is no bug tracker. When asked why, the answer is always some variation of “we don’t leave known bugs unfixed.”

Postfix is neither trivial nor dead, so there are other models possible.

ScottK,

That is really interesting. I’d love to know there’s a counterexample out there, but is it a definitional issue? If one defines “bug” narrowly, it might be possible to fix every bug (though I confess skepticism even then), but sometimes that’s just a way of saying “we don’t track enhancements or feature requests as bugs”. Also, if you don’t have a bug tracker, maybe that just discourages some people from filing bug reports. I.e., how do you even know what the set of “known bugs” is if you don’t have a tracker? Is the report rate just so slow that it’s possible to keep track manually on the mailing list?

By the way, does this mean all the upstream bugs in the list at https://edge.launchpad.net/ubuntu/+source/postfix/+bugs are fixed already? Real question, not rhetorical; I haven’t looked at the list in depth.

Anyway, thanks for the observation. It is certainly a different model; as you can tell, I’m not quite willing to believe the claim that a non-trivial project leaves no known bugs unfixed, but I wouldn’t reject it out of hand either. If someone who reads these comments is a Postfix user, let us know :-).

https://bugs.edge.launchpad.net/ubuntu/+source/postfix/+bug/501364

Recent; trivial patch (according to the submitter); not applied. Again, I don’t know whether what the submitter says is accurate, or whether this is a bug at all. But it is being tracked in a bug tracker — at Launchpad.

So in a sense, there is no such thing as a project without a bug tracker anymore, hmm. The project may or may not have its own tracker, and the developers may or may not think they need it, but someone somewhere is tracking bugs anyway, and one of those places will probably become the default “list of record” in the absence of anything more compelling.

The number of bugs is not correlated to the number of users because fixing bugs changes the number of bugs.

I think if you look at other types of engineering: airplanes, buildings, etc. they might agree that there is no one perfect way to design something, but that if it did crash it would be a bad thing. If you look at many of Ubuntu’s bugs in launchpad, at least 50% look bad. And lots of people are complaining about Ubuntu’s bugginess. I believe working aggressively on the bug list can help improve the perception and the problem.

And there is a problem about letting bugs linger. The fact that the iPod w/ iTunes doesn’t work on Linux is a barrier that affects 200M people and is still broken 8 years out. As long as a community is churning through its bugs, then it is moving the codebase forward in all important directions. Now in Ubuntu’s case, each bug needs to be verified, and then shepherded into the upstream codebase. Perhaps focusing on the number of unverified bugs should be Ubuntu’s goal. Once you’ve handed it off to the proper upstream developer and answered his questions, then Ubuntu has completed an important job. It would be interesting to try to get that number to zero as a start.

BTW, you are thinking about the Postfix situation wrong. Postfix are basically saying that when a problem comes in, they either fix it immediately or decide they won’t fix it. Launchpad might have a bug report, but it doesn’t make it a part of their workflow. The point is that the launchpad bug report eventually turns into something like an email list discussion and they can keep track of things in there. It is only when you don’t address all of your issues right when they come in that you need a bug tracker as opposed to just using email-type communication.

BTW, I have found that Akismet does a great job dealing with spam and that captchas are unnecessary.

@Keith

I’m not saying people shouldn’t fix bugs. Of course they should. But we need to understand that triage is the natural state of affairs.

Driving a widely-used system’s bug list to zero? Good luck with that :-). I don’t think it’s going to happen.

You wrote: “The number of bugs is not correlated to the number of users because fixing bugs changes the number of bugs.”

They will always come in faster than you can fix them, because what causes them to come in is people encountering them. The more users you have, the more “surface area” the software is exposed to, so the more flaws will be reported. It’s not necessarily that more flaws will be found, it’s that more will be reported, because a growing user base increases the probability that at least one of the users who encounters a particular bug will report it — because a larger number of users total are encountering that bug now.

If Postfix decides not to keep a permanent, easily findable record of bug reports that they’re not going to fix right away, that’s fine, but then they’re practicing the “lower the number of bug reports by discouraging filings” method. I don’t know that that leads to better or worse software, but it certainly makes it harder for conscientious reporters to find duplicates.

Karl,

Triage is the normal state of affairs, I agree. Especially in a codebase adding code.

There is a curve that levels off where adding more users doesn’t appreciably increase the surface area used. If I selected 1,000 random people around the world and looked at all their bugs, it would cover the vast majority of the bugs in the Ubuntu bug database.

In any case, Ubuntu is filled with bad bugs, so any theoretical analysis doesn’t matter. They might not be able to hit zero bugs, but they can make up many other good goals. I was suggesting zero bugs not also linked up to the upstream buglist. There are many interesting goals that Ubuntu could set over time.

If I could change one thing about the free software culture, it would be to push more for them to think about crashes the way airplanes designers do. When you have 100 million lines of code, you need to push for high quality or it will fall over constantly.

Some bug statistics gathered by Stephen Turnbull about another project, that seem to support the hypothesis (though a broader survey would of course make a much stronger case):

http://lists.gnu.org/archive/html/emacs-devel/2010-06/msg01025.html

Stephen made that post in a thread about the number of open bugs in the Emacs bug tracker. Money quote: “Sure, you can and should try to reduce the number of open bugs in Emacs, but I think you’re going to end up needing to accept 4-figure counts just like everybody else.”

From Joe Brockmeier at OStatic:

http://ostatic.com/blog/fixing-the-perception-of-bugs

I was referred to this post on a mailing list at work. I am wondering if you have any updates to your insight almost 5 years on?

Harish

None come immediately to mind — er, except that I still think the observation is true :-). I hope you enjoyed the post.